Let’s put the success of Radio, LL Cool J’s debut album, in perspective. By mid-1986, the precocious teenager from St. Albans, Queens, had received a Gold plaque from the RIAA. Only three other rap acts—Run DMC, The Fat Boys, and Whodini—had received one for an album. And they were groups, not soloists. Critics fawned over LL’s command over the mic and seemingly proclaimed him as the first successful solo rapper, leading the next generation of hip hop alongside fellow Queens natives Run-DMC. The boy who was yet to get out of his teens was going mainstream, notably the first solo rapper to appear and perform on American Bandstand. And he accomplished all of this, in a world where MTV was ubiquitous, without a single music video out.

So, the possibilities were endless as LL went back to the studio to work on his sophomore album. He was yet to exhaust the limits of his powers and resources. How much bigger and better could this new record get?

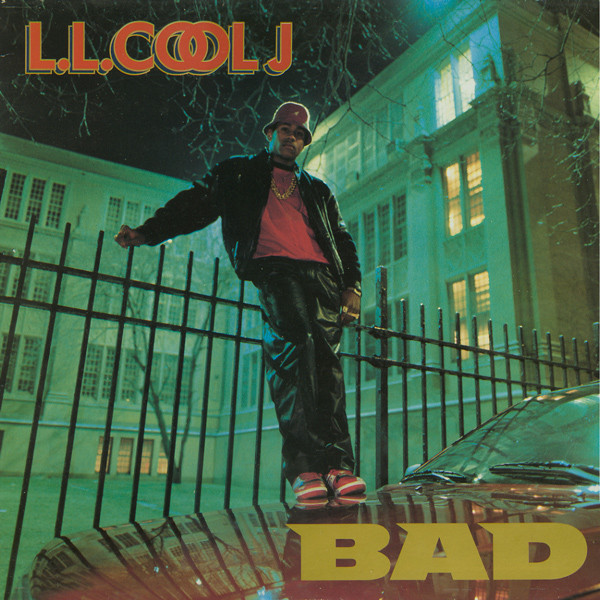

LL Cool J’s second album has the word BAD printed at the bottom right of the front cover. It actually isn’t a word, but an acronym for “Bigger and Deffer.” And he couldn’t have started the album better than with a track that not only was the album’s first single, but also yielded LL’s first music video. The beat for “I’m BAD” is anchored in the bridge by the Q2B siren and a sample of the famed S.W.A.T. TV series theme, with eight bass notes inspired by the theme song of the Courageous Cat and Minute Mouse cartoon series layered over earth-shattering kicks. It’s the perfect ominous soundscape for LL to deliver four intensely hot verses brimming with overwhelming hyperbole and memorable similes.

And trust LL Cool J to occasionally spit venom in the process. With some scratching, a single horn spurt, and a few funk guitar licks for the consequently scantily-clad viciousness of the double hi-hat drum beat, LL in “The Breakthrough” only needs one long verse to brutalize whoever he thinks is beneath him. “Don’t you know you’re just a worker, and your boss is my man? / LL this, LL that, soon as I walk in the place/I wanna take my gun and shoot it in your mother******’ face!”

All the while, there is some improvement in his raps. His delivery is remarkably faster, yet nimble; and he has more weapons in his arsenal, like the alliteration in “Ahh, Let’s Get Ill”. There’s still some of the youthful exuberance that’s so abundant in Radio, and it’s quite a welcome characteristic. The topical variance in Radio is found here as well. “Kanday” details LL’s obsession with his girlfriend. “The Bristol Hotel” becomes a breeding ground for a multitude of nymphomaniacs. And “The Do Wop” is a tale of a typical day in the backstage life of LL Cool J, which all seems so real until it’s revealed it’s but a dream at the end of the song.

However, as good as those songs are, “My Rhyme Ain’t Done” shuts the other numbers down in pure entertainment and hilarity, as LL goes through interwoven plot lines to create a story. In his tale, the Pope appeals to God to raise Michelangelo from the dead and create a painting of him; he starts a band with Spider Man, the Incredible Hulk, and Charlie Brown; hangs out with Mickey Mouse to have an orgy with a pair of freaks; is inadvertently offered the sticky-icky by a Native American chief; and lusts after Alice Kramden of The Honeymooners. Yeah, it’s outlandish, but it’s pretty creative and funny.

So with the hardcore raps interspersed with the respite of novelty topics, a considerable variance in production should be expected. Def Jam co-founder Rick Rubin had been the sonic architect of Radio, primarily dressing up LL’s lyrics with lean yet livid drum machine-based production. His success led him to work on two other landmark projects in 1986. One would turn out to be Run-DMC’s most commercially and critically successful album (Raising Hell), and the other was the debut album of another Def Jam act, the Beastie Boys (License to Ill). But by 1987, Rubin was nowhere to be found, his general disaffection with the label he helped build eventually driving him away from it. And the other co-founder of Def Jam, Russell Simmons, wasn’t too thrilled about the void left behind. Fortunately for him, though, he had come across this production crew referred to as the L.A. Posse, consisting of Darryl “Big Dad” Pierce, Dwayne “Muffla” Simon, and DJ Bobby “Bobcat” Ervin.

LL was also glad to step in with his own contributions. It’s a good thing he did. Gone, for the most part, is the skeletal feel prominent in Radio. Yes, there are still vestiges of it in “Kanday,” “The Bristol Hotel” and “The Breakthrough.” But the hard-hitting beats in Bigger and Deffer are fleshed out with screeching guitars, thick basslines, and choice samples. There’s the aforementioned “I’m Bad” and “Get Down,” but there’s also the rap remake of Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode” with “Go Cut Creator Go,” which is a DJ dedication piece, Cut Creator scratching with all his might amidst the uproarious electric guitars and the words of his homeboys cheering him on. “.357 – Break It On Down” has this sinister low bassline joined occasionally with brief moments of wah-wah guitar licks. “Get Down” comprises a portion of the Shaft theme over a hyper drum machine and vigorous scratching. And “The Do Wop” is exactly just that: a number with the vocals of a doo wop group looped over a subtle drum machine. Overall, this is a more fulfilling production job.

Thus it is only proper that a certain track in this album became an unexpectedly phenomenal success.

Neither LL Cool J nor the L.A. Posse came up with the original melody and beats for “I Need Love.” It just so happened that an associate of LL’s came across an instrumental named “Zoraida’s Heartbeat”—also known as “Zoraida’s Heart”—composed by a Jayson Dyall from Brooklyn. The tape containing the instrumental made its way to LL Cool J and his crew, who interpolated said instrumental into a syrupy organ-driven beat.

“I Need Love” succeeded where “I Can Give You More” didn’t; the production fits the lyrics like a glove. While the sparse piano notes and jarring drum machine fails to convince the listener of the lyrical sentimentality in “I Can Give You More,” “I Need Love” is slowed down, the simple sequence of the organ notes allowed to seep in and segue into the choral subtlety of the strings. It makes LL’s lyrics stand out a lot more than before, and he truly delivers in top form. In a half-whispered voice, he expresses his consuming search for true love, and what would happen when he finds that special someone. The third verse is particularly ingenious, employing cryptic and subtle phrasing to paint a beautiful picture of a love scene.

I watch the sun rise in your eyes

We’re so in love, when we hug, we become paralyzed

Our bodies explode, an ecstasy unreal

You’re as soft as a pillow, and I’m as hard as steel

It’s like a dream land, I can’t lie, I’ve never been there

Maybe this is an experience that me and you can share

Clean and unsoiled, yet sweaty and wet

I swear to you, this is something I’ll never forget

I need love!

Consequently, “I Need Love” became hip-hop’s first successful love ballad, peaking at #14 on the Billboard pop singles chart. It made LL Cool J the pioneer of the rap ballad, and even years after scores of emcees have followed his template, he remains its premier practitioner. LL had finally lived up to his moniker, and his lothario image would be a worthy—and sometimes conflicting and maligned—counterpart with his hardcore persona throughout his career.

There’s no doubt that there’s some prime-time, top-caliber boasting in Bigger and Deffer. Some of his most memorable lines, particularly in “I’m BAD,” can be found here, as well as some lesser-known gems, like when he amusingly proclaims in “.357 – Break It On Down” that he’s “better than Better is; badder than Badder is!”, or that he’s “badder than Napoleon, Hitler or Caesar!” in “The Breakthrough.” And there are other points of innovation apart from “I Need Love.” Just like the post-“Dangerous” acapella in Radio is an early example of the hip hop skit, the last track in Bigger and Deffer is thirty-one seconds of LL celebrating the completion of another album with his homies, symbolizing another prototype: the outro.

Some of LL Cool J’s boasts, however, tend to be borderline excessive and annoying. He had not quite crossed that threshold yet, but in a few numbers here, he was pretty close. “Ahh, Let’s Get Ill” is the best example. What could have been one of the hallowed examples of rap alliteration becomes an occasionally tiring exercise in self-exultation, as LL borrows certain pronouns way too liberally: “I’m the little-girl liker, legendary writer / Let’s see, I never lost, ‘cause I burn like a lighter / My love is long, and my lyrics rock loud / […] /I’m the ladies Love, lyrical lord in the club/Ladies love, the man you dream ooooooof!”

Critics were quick to note the increase in bragging. Some of the people who had heaped praises upon LL Cool J’s debut generally marked Bigger and Deffer as a follow-up that didn’t quite match the former’s ferocity. But in retrospect, overall Bigger and Deffer improved on the strengths of its predecessor—and, of course, it delivered “I Need Love.” And it was more commercially successful.

For the first time, LL Cool J had singles that broke through the pop charts, and the album, which peaked as the #3 album in the country, took about half the amount of time of Radio to go Gold. (It would be certified double Platinum by the end of 1987.) With Bigger and Deffer, LL solidified his position as perhaps the top gun in the rap world. And unsurprisingly, his success, his excesses, and his ego would generate some powerful detractors in the ensuing years.